Robertson Davies, that most delightful Canadian novelist, playwright, and essayist, quipped that most people don’t want to read books, they want to have read books—to enjoy the distinction of being well-read without the bother and work of reading.

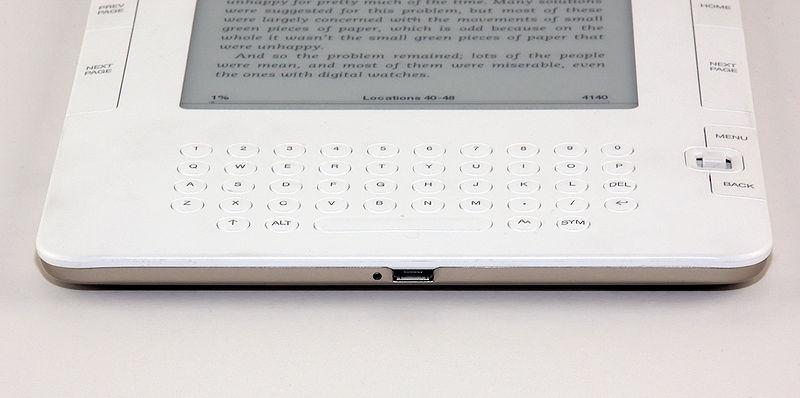

Never was that attitude made more evident than by that dreadful feature in e-readers, the progress bar. For those of you who don’t have an e-reader, a progress bar is a display of how much “progress” you have made in a book.

For example, I have a “book” open on my e-reader, and it reports that I have read 19% of the book and have 3 hours and 48 minutes left to go before finishing up. This, purportedly, is how much “progress” I have made in this book.

This is nonsense.

You can peruse, browse, or study a book. Speaking metaphorically, you can pour over or even devour a book. But you don’t progress though a book. Perhaps you would say that you have made progress in studying a book or made progress working though a textbook. But you do not make “progress” in a book.

The very idea of progress implies getting through to the end—conquering something and putting it 100% behind you. It is a thoroughly modern, technocratic notion of realizing a better, more complete, more perfect condition.

This is an entirely backward approach to books, or at least serious books that take up the permanent questions about the good, the beautiful, and the just. You don’t get to the end of your first reading of a book like George Eliot’s Middlemarch or Dostoyevsky’s Brothers Karamazov, or, say, Plato’s Republic, and say, ah, done with that one!

And, yet, that’s exactly what the progress bar suggests, you have made 100% progress! Zero minutes left! You are done! You have consumed the book and are done with it.

This isn’t the attitude appropriate for serious fiction: a first reading of a great book like Middlemarch is a bare introduction, a first taste to guide a more intelligent second, third, or fourth reading. I dare say no one can be 100% done with Middlemarch, which Virginia Woolf described as “one of the few English novels written for grown-up people.”

I’m not ignoring the fact that it is sometimes handy to know one’s reading rate—for example, if one is reading background materials for a meeting and trying to gauge how much preparation time to budget. However, that kind of reading for a deadline must be a tiny fraction of the reading done on e-readers.

This pervasive attitude that reading is something we “get through” or consume for entertainment makes great texts like Middlemarch harder to read and savor. After all, savoring a book will bump up the progress bar’s estimate of your time to completion!

Tufts University scientist Maryanne Wolf studies how different ways of reading affect the brain. Her work gives insight into the consequences of this attitude to reading. Here’s what she told the Washington Post about what she’s heard from English professors about today’s college students:

They cannot read Middlemarch. They cannot read William James or Henry James,” Wolf said. “I can’t tell you how many people have written to me about this phenomenon. The students no longer will or are perhaps incapable of dealing with the convoluted syntax and construction of George Eliot and Henry James.

Such a shame! Eliot’s Middlemarch was the Games of Thrones of its day, serialized over 1871–72, each volume as eagerly anticipated as Game of Thrones fans anticipate the next Game of Thrones episode.

The Post story reports:

Word lovers and scientists have called for a “slow reading” movement, taking a branding cue from the “slow food” movement. They are battling not just cursory sentence galloping but the constant social network and e-mail temptations that lurk on our gadgets—the bings and dings that interrupt “Call me Ishmael.”

Getting rid of that terrible “reading progress bar” would be an important early step for a slow reading movement.