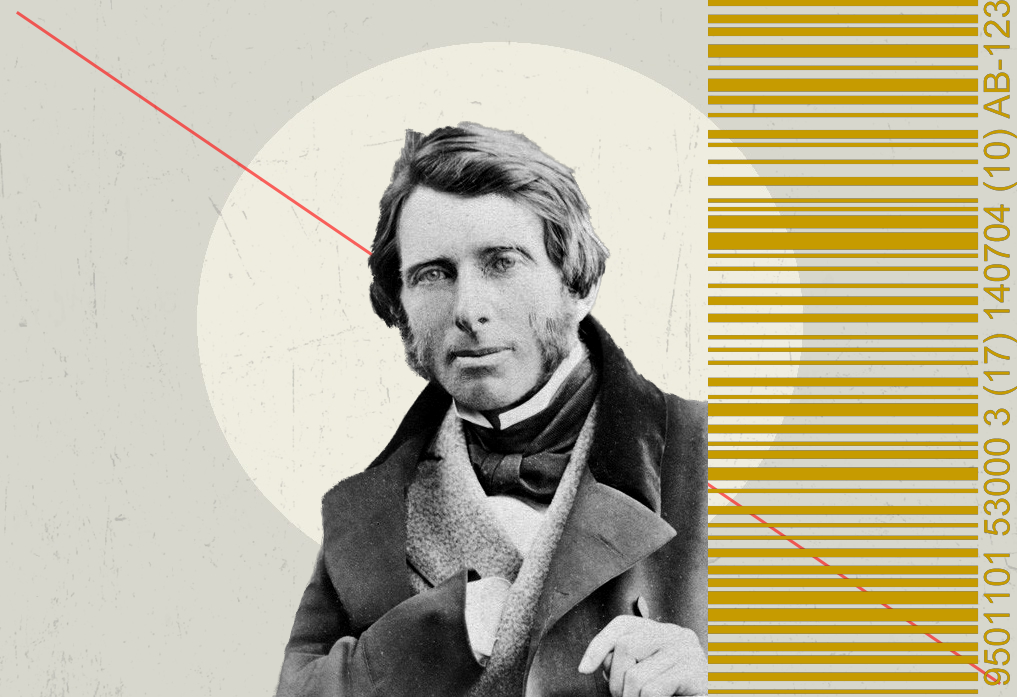

John Ruskin’s keen observations on living coherent and integrated lives sheds some light on our modern practice of “cause marketing” and “consumption philanthropy.”

Cause marketing is a force in contemporary philanthropy. It’s so ubiquitous that any single campaign is almost unremarkable—though some do still manage to catch the public’s attention.

For the nonprofits benefiting from it, cause marketing (or, as it is sometimes called, “consumption philanthropy”) undoubtedly seems like a great tactic, and its proceeds are a welcome windfall. For consumers, too, cause marketing campaigns can seem pretty great, since they provide a way of “doing good” by doing pretty much the same things we were going to do anyway.

Despite its upside, consumption philanthropy is not an unalloyed good. I share the concerns of critics who argue that the practice of philanthropy should be separate from the practice of consumerism.

That said, consumption philanthropy does seem built on an assumption I share: that our actions and decisions as consumers should not be considered separate from our role as citizens and neighbors.

Put simply, the things we choose to surround ourselves with signal, to varying degrees, who we are and what we value. This is obvious to any twelve year-old who wants the same sneakers his friends have, it’s obvious to the upper middle class woman pushing her cart down the aisle at Whole Foods, and it’s obvious to the nun who takes a vow of poverty.

The goal of most cause marketing campaigns is to associate new or different signals with a given product than we would ordinarily associate with that product. Buying a pair of shoes from Tom’s doesn’t just mean you’re the kind of person who wears shoes; it also means you the kind of person who “takes a stand on issues that matter.”

It’s not hard to see why consumers would welcome cause-marketing practices. In our age of unfettered consumption, the relentless cycle of acquisition and discarding will wear you down and leave you feeling empty. Cause marketing seems to offer the chance to introduce a certain coherency to our lives—to combine our purchasing practices with our convictions about, say, saving polar bears.

The quest for coherency is nothing new. It just so happens that there are other, more fruitful models than what consumption philanthropy provides.

In a recent essay about the 19th century social critic and philanthropist John Ruskin, Baylor University professor Alan Jacobs observes,

The great quest of Ruskin’s life was to amalgamate disparate experience: not to allow the various aspects of life to sit separate with one another, as though our prayers have nothing to do with our purchases, or our arts from our labor, but rather to bring all of them together in a healthy, vibrant symbiosis.

To weave these strands into a cohesive whole, says Jacobs, is to live in an “integrated way.”

Ruskin was blissfully unfamiliar with modern cause marketing campaigns. For him, everyday objects would not have been imbued with value because of their tenuous association, at the time of purchase, with some nonprofit or social cause. For Ruskin, a champion of beauty and handcrafted objects, buying shoes might indeed represent a moment of moral and aesthetic consequence. But he never would have believed that the worth of shoes could be improved by the fact that buying them will provide a child in a third-world country with a similar pair.

Objects derive value from the care and attention invested in them, both by their maker and their user. “I cannot but think it an evil sign of a people when their houses are built to last for one generation only,” Ruskin wrote.

I think it is fair to draw similar conclusions today, when our shoes and clothes and fast food cups and cars and, indeed, our buildings are meant to be used for a brief span and then replaced. In our throwaway culture, in which we surround ourselves with disposable, readymade goods, we rarely invest in the thoughtful production, maintenance, and continual use of objects.

One could argue that cause marketing campaigns do encourage both companies and consumers to pay more attention to the context of their actions—how their decisions redound on others. Which is great. Unfortunately, they also manage to reinforce our addiction to consumption, recasting vice as virtue.

Well-made, beautiful objects do not need to be associated with a cause to drive consumer interest: their own integrity, beauty, and usefulness are, or certainly ought to be, cause enough to possess them. This is not to say that companies should curb their charitable impulses. I wish every businessperson in this country would give away money on a regular basis. But as we seek to live in more “integrated ways,” the mash-up that is “consumption philanthropy” represents the wrong kind of integration.

“For we are not sent into this world to do anything into which we cannot put our hearts,” Ruskin wrote. It is a high standard, one which consumption philanthropy—and, it should be noted, much else besides—fails to meet. But when it comes to philanthropy, which means, literally, “the love of humankind,” our hearts must always be in it.