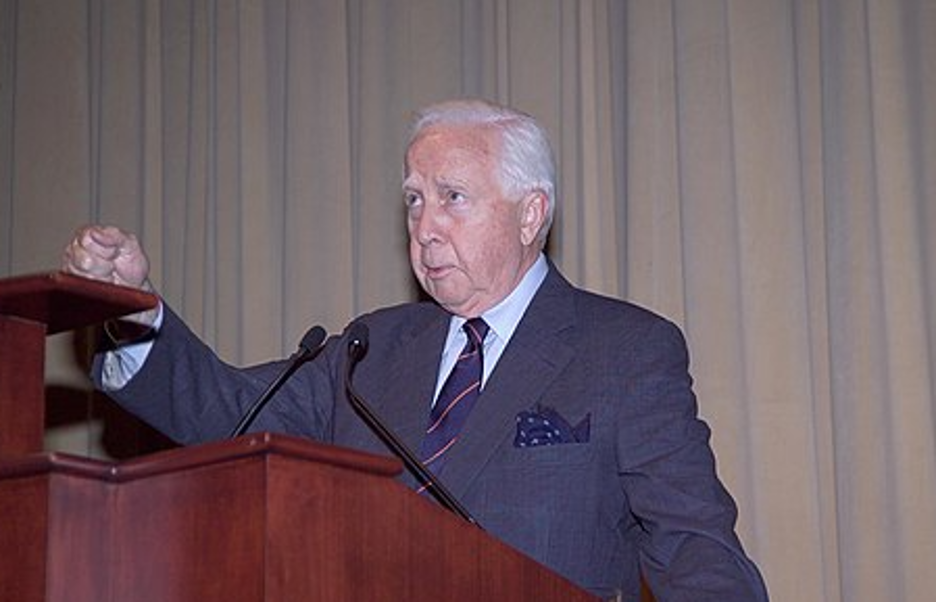

Remembering “the voice of history.”

In Whatever Happened to Tradition?: History, Belonging and the Future of the West, historian and Daily Telegraph columnist Tim Stanley argues that our future is a dim one indeed unless we have a proper sense of our political, social, and religious tradition. Since the Enlightenment, he argues, we in the West unfortunately have been battling with each other over whether or not it is necessary—required, some say—to emancipate ourselves from our history to be truly free.

I thought of Stanley’s contention upon hearing earlier this week of the passing of David McCullough—who “gained critical acclaim for his knack for bringing American history to life in his books and the television screen through dramatic narratives that created colorful pictures of figures,” as The Wall Street Journal accurately put it.

Undoubtedly, McCullough’s work made a valuable contribution to understanding of the history of American and all the West. Understandably, his writing is being praised without reservation. But he should also be remembered for his full-throated defense of strong K-12 American and world history education.

He had an admirable passion for all of us knowing who we are and how we became that way—and what both who we are and how we became that way might mean for both our future and that of those who follow us.

In 1987, Milwaukee’s Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, where I worked, established the Bradley Commission on History in Schools. The commission included 16 of the most-respected members of the history profession, including former presidents of each of the major professional organizations in history, and a number of award-winning history teachers and writers.

During the next year and a half, it discussed, developed, and nationally distributed a series of recommendations for the teaching of American, European, and world history in the nation’s K-12 curriculum. They are in its final report, Building a History Curriculum: Guidelines for Teaching History in Schools.

Later, several Bradley Commission members—including its chair, noted American historian Kenneth T. Jackson of Columbia University—created the National Council for History Education (NCHE). McCullough proved to be an invaluable resource for the Bradley-supported NCHE, participating in much of its early programming, including speaking at many of its events.

Given his reputation and popularity, of course, McCullough told stories that only he could tell—and in that familiar voice which coerced attention, and rewarded the giving of that attention.

He wrote 12 great books, about presidents, the Wright brothers, the building of the Brooklyn Bridge, and many other topics. The Journal quoted him as saying in 2007 that history “is most appealing to anyone, but particularly the young, when you take a defined subject and bring it to life by telling the story.”

In fixing the Presidential Medal of Freedom around McCullough’s neck in 2006, President George W. Bush respectfully called him “the voice of history.” In fact, through his life’s work, McCullough gave voice to a respectfully proper sense of our political, social, and religious tradition.