Charles Dickens is the English author we most closely associate with Christmas—so much so that when his death was reported, one young English girl is said to have exclaimed, “Dickens dead? Then will Father Christmas die too?”

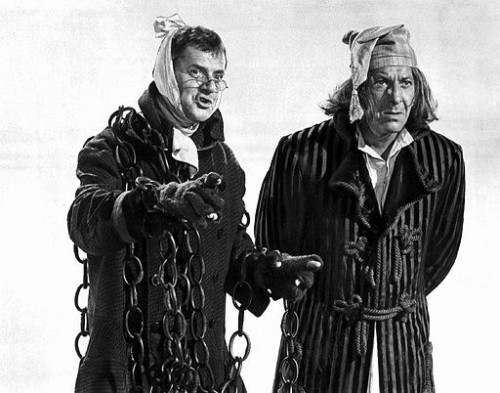

Dickens’ five Christmas novellas are full of ghosts, goblins, and phantoms—and are so because a great theme of all of these stories is remembrance and recollection, and the role of memory in shaping our characters. Ghosts and phantoms bear memories of the past, and long dead people come back to the present in spectral form.

The most famous of Dickens’ Christmas novellas is his first, A Christmas Carol, written in 1843. The Ghost of Christmas Past confronts the recalcitrant sinner Ebenezer Scrooge with memories of his young days as the Ghost endeavors to soften Scrooge’s hardened heart. As we learn, as a boy and young man, Scrooge suffered the deaths of his mother and sister, and the unkind treatment at the hand of his father; when we see how much he has suffered, the Scrooge who seemed so despicable in the first pages of the novella becomes a rather sympathetic figure. It turns out that Scrooge’s understandable efforts to forget his unhappy past explain in large part his hard-heartedness; only when Scrooge is able to abide with the painful memories of his past can he sympathize with the misfortunes of Tiny Tim and others in the present.

The darkest of Dickens’ Christmas ghost stories is his last, The Haunted Man and The Ghost’s Bargain, written in 1848. The Haunted Man reverses A Christmas Carol: While the Ghost of Christmas Past confronts Scrooge with memories that Scrooge has deliberately put out of mind, in The Haunted Man, a Phantom comes to the gloomy Professor Redlaw with an offer to erase painful memories upon which the professor has dwelt for many years.

As we meet Professor Redlaw on Christmas Eve, he laments how the season of Christmas stirs memories:

“Another Christmas come, another year gone! … More figures in the lengthening sum of recollection that we work and work at to our torment, till Death idly jumbles all together, and rubs all out.”

In this grim mood, Professor Redlaw accepts the Phantom’s offer to forget how, as a youth, he was betrayed by friends and suffered a beloved sister’s early death. Unburdened of these painful memories, the Professor discovers to his horror he lacks the psychic resources to be compassionate to others.

Through the intercession of a Christ-like figure, the Professor is restored to himself, and he realizes that:

...Christmas is [the] time in which, of all times in the year, the memory of … sorrow, wrong, and trouble in the world around us, should be active with us…

Surely many people share Professor Redlaw’s feeling that Christmas brings up past wrongs and disappointments: A letter published in Carolyn Hax’s advice column this month began with the sentiment, “I hate Christmas. I mean really, really hate it,” and continued with the letter-writer’s litany of wrongs and slights of which Christmas put her in mind.

Yet, as Dickens’ Christmas specters suggest, it’s the disappointments, slights, and mischances we’ve suffered that often enable us to open our hearts to others, and to sympathize with their misfortunes. It is the hurts we have endured that open us to fellow-feeling and communion with others, and with the joy attendant on fellowship with others.

May we be rich in memories—unhappy memories as well as happy ones—this Christmas, and rejoice in the season.

Merry Christmas!