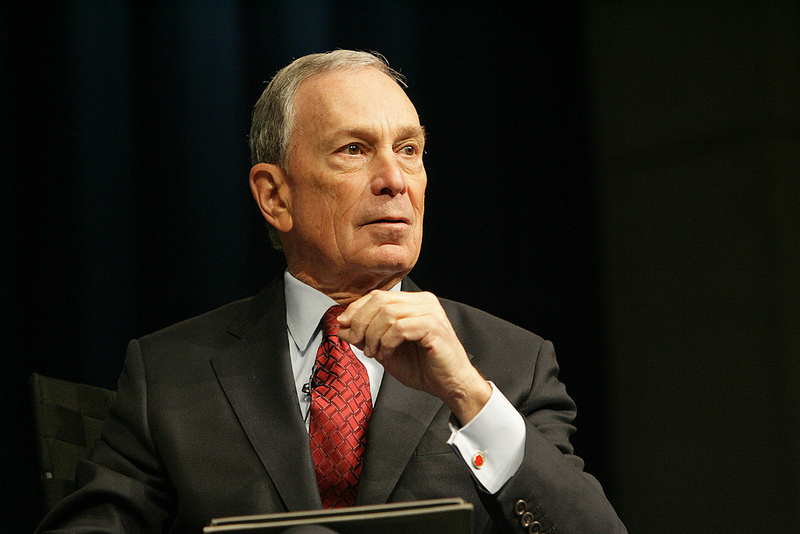

Michael Bloomberg is missing the point: what we need right now is not more data, but more debate.

Over at Inside Philanthropy, David Callahan makes a noteworthy argument about Michael Bloomberg’s Annual Letter on Philanthropy. The ex-mayor’s Letter gives insight into the motivations and goals of one of the country’s most prolific and influential donors.

This year Bloomberg placed a special emphasis on the importance of data. Bloomberg wants to position his data-driven, technocratic brand of targeted activism as the alternative to the rise of Trumpian ‘alternative facts’: “Data doesn’t give us all the answers,” Bloomberg admits, “But data and facts anchor our thinking to reality at a time when political debate is increasingly untethered to them.”

For anyone who follows Bloomberg, this is hardly surprising. What is surprising is that Bloomberg apparently thinks this commitment to measurable success and rational planning constitutes some sort of protest.

As Callahan argues, however, this approach misses the point. It is not enough to assert the value of data at a time when what is fraying the social fabric is not disagreement over metrics but in fact a fundamental clash of “underlying values.” Callahan ominously summarizes:

There’s little consensus in America today over basic normative questions like how much we should help the least fortunate among us, who should be included in our democratic polity with full rights, the degree to which we should regulate market actors to protect the public, how interdependent America should be with other countries, and what ecological constraints humans are confronting. Increasingly, there’s no longer even agreement over basic facts.

In light of these disagreements, what’s needed is a more politicized approach to philanthropy, in the best sense—that is, philanthropic leaders like Bloomberg have to be willing to make their case to the country, they have to be willing to “really [take] sides in this war of ideas” that the right has so heavily invested in for the last half-century.

That seems right, but we can go further.

Besides data, Bloomberg’s letter also stressed the role of cities in blazing a path beyond the current stalemate. “The majority of the world’s people now live in cities for the first time in history,” Bloomberg notes, and cities are increasingly being seen as “dynamic” centers of resistance to federal dysfunction.

City halls, Bloomberg suggests, prove “more nimble, more pragmatic, and more responsive to public concerns than national governments.” As evidence he cites the America’s Pledge initiative, a coalition including some 450 US cities (as well 300 universities and 1,700 corporations and businesses) promising to meet America’s carbon-reduction goals under the Paris climate agreement, despite President Trump’s withdrawal from that treaty in 2017.

The turn to cities as the vanguard of the left’s alternative social vision carries real risks, however.

First, it miscategorizes the nature of the problem. It’s not merely that Washington isn’t ‘nimble and pragmatic’ enough to deal with national issues—it’s that we can’t even agree what the important issues are. The preoccupation with ‘rational’ politics suggests that Bloomberg believes that if only everyone were looking at the same set of numbers, consensus would be inevitable. But Pew data from early 2018 suggest larger-than-ever partisan divides on fundamental issues like Russia, immigration, and free-trade; whatever it is that splits our politics, it seems safe to say it’s not just a different set of data points.

Second, Bloomberg’s emphasis on cities risks exacerbating exactly the same rural-urban divisions that so defined the 2016 election. By focusing on metropoles, Bloomberg is of course just following the data—that’s where his program of environmental regulation, civic art and infrastructure investment, and tobacco restrictions are most likely to find a receptive audience. But what do such efforts say to voters like these, recently interviewed by the UK’s Channel 4, who stubbornly insist that any critic of Trump is just a delusional swamp monster who needs to “get back to Middle America”? Heartland die-hards like these are unlikely to be persuaded by Bloomberg’s measured appeals to shared good will and data-driven deliberation.

Philanthropy has a role to play here, as usual, as a bridge-builder and an incubator of civic familiarity. But as part of that mission, it shouldn’t shy away from encouraging certain fights. After all, structuring a debate in which the participants are actually engaging with one another, rather than talking past each other, is one of the high achievements of civil society.

Unfortunately, Bloomberg’s letter once again shows that liberals are talking primarily to themselves, while Trump’s die-hards clearly have no patience for Bloomberg’s vaunted ‘facts.’ Liberals won’t escape this problem by strategically retreating to the cities (the last election proved that), but only by really engaging in the battle of ideas.

What we need right now is not more data, but more debate.

Photo credit: World Bank Photo Collection on Visual Hunt / CC BY-NC-ND