Then beware: For the second time in three months, no less a defender of governmental benevolence than the New York Times has published a left-of-center author who raises the specter of Doubt.

This debate affects the tax-exempt world for two reasons. First, less government aid to the needy directly affects charities and funders who serve the same populations. Second, the Doubters of the gospel of government have begun to criticize government’s tax-exempt allies.

In late July came the first of the Times’ Doubters, pollster Stanley Greenberg, who explained that his polls and focus groups reveal that the Democratic Party’s current difficulties involve more than short-term political set backs; they represent “a full-blown crisis of legitimacy” for liberalism. Voters, Greenberg warns, “feel ever more estranged from government.”

This isn’t the place for partisan analysis of Greenberg’s diagnosis of the Democrats’ woes and his suggestions for reframing the political debate in their favor. I want to focus on the deeper, tectonic issues that he raises with considerable insight, because those issues are central to the question of why America has a nonprofit sector, and what its proper role should be.

Greenberg essentially boils down Americans’ complaints with government to two: (1) “Government works for the irresponsible, not the responsible.” (2) a new class, in and out of government, uses government to enrich themselves. On the first point, Greenberg’s voters tell him they disapprove of bailouts large and small, whether the beneficiary is a Wall Street firm whose speculations have gone south, a homeowner who bought too much house for his income, or an immigrant who entered the country illegally.

On the second point, Greenberg quotes a voter saying, “There’s just such a control of government by the wealthy that whatever happens, it’s not working for all the people; it’s working for a few of the people.” Another voter declares, “We don’t have representative government anymore.”

To his dismay, Greenberg finds similar results throughout Europe and Canada, which explains why center-right parties are outdistancing center-left parties, even though economic hardships should make it easy to sell voters on more government aid to the less fortunate.

In response, some on the left will say that ordinary citizens are fools, duped by anti-government opinion leaders who are either themselves fools or puppets of plutocrats (cue the familiar refrains about the backwoods Sarah Palin and the nefarious Koch brothers, respectively).

My own favorite in this condescending line of thought is a comment made on the New York Times website during the Obamacare debates. One Barbara M. Cohen was livid at Pew Research polls that showed Americans who earn under $50,000 per year opposed nationalized health care, while those making more than $100,000 supported it:

Could it be that the working class does not know what is good for it? … Could it be that it can be easily fooled – witness the death panels of Ms. Palin – and lacks the judgment needed to make a democracy work? … Can we not see that time after time the working class gets worked up over its social resentment of the “educated elite” and votes against Dems and for Tax Cutters?

With impressive blindness, Cohen proceeded to demonstrate why voters just might resent people like her. She concluded,

In Singapore they have meritocracy, enlightened leadership by technocrats and a guided democracy that never degenerates into mob rule. And they have one of the best health care systems, an education system that puts us to shame, a public transportation system that business schools write case studies about. In the U.S.? We have Lou Dobbs, Sarah Palin and a working class that they whip up into a frenzy.

To his credit, Greenberg isn’t ready to end our experiment in self-government in favor of “guided democracy.” He recognizes that skeptics of government have good reasons for their views, because a fundamental disconnect exists in our society: “politicians take care of themselves and party interests, while government grows remote and unresponsive, leaving people feeling powerless.”

Here is the connection to civil society’s tax-exempt platoons, which in America have typically begun life spontaneously, as local citizens band together to solve problems. By contrast, large centralized entities inherently grow remote and unresponsive. They don’t just leave the people who aren’t at the center feeling powerless; they leave those people actually powerless, because authority and initiative have been appropriated by the central masters.

That’s why the best charities and businesses, as they grow, try hard to keep their operations decentralized, so that everyone will be able to take the initiative when an opportunity presents itself. My son’s Cub Scout den, for instance, is part of a vast global organization, but his den leader doesn’t feel powerless. Even the best militaries, for all their size and hierarchy, work this way. The U.S. Marine Corps demands that commanders cultivate “decentralized decision making” up and down the ranks.

Our second Times author to stumble onto this fact of human nature is columnist Anand Giridharadas, who last week suffered a serious intellectual shock: “Here is something I never thought I would write: a column about Sarah Palin’s ideas.” Seems in a recent speech Palin

made three interlocking points. First, that the United States is now governed by a “permanent political class,” drawn from both parties, that is increasingly cut off from the concerns of regular people. Second, that these Republicans and Democrats have allied with big business to mutual advantage to create what she called “corporate crony capitalism.” Third, that the real political divide in the United States may no longer be between friends and foes of Big Government, but between friends and foes of vast, remote, unaccountable institutions (both public and private).

Again, I don’t care about partisan questions such as Palin’s fitness as a presidential candidate, etc. What matters here is that another Times author, with credentials from Oxford and the Aspen Institute, admits that the old-time hymnbook from which his readers have long sung is out of date: America is not a battleground between two simple groups, one that supports big government and another that supports big business. Rather,

Palin may be hinting at a new political alignment that would pit a vigorous localism against a kind of national-global institutionalism. On one side would be those Americans who believe in the power of vast, well-developed institutions like Goldman Sachs, the Teamsters Union, General Electric, Google and the U.S. Department of Education to make the world better. On the other side would be people who believe that power, whether public or private, becomes corrupt and unresponsive the more remote and more anonymous it becomes; they would press to live in self-contained, self-governing enclaves that bear the burden of their own prosperity.

Amusingly, both Giridharadas and Greenberg seem to imagine this idea is new. Perhaps they’ll someday stumble upon thinkers like Robert Nisbet and Alexis de Tocqueville, who made such arguments before our Times writers were born. A glance at market-loving, now-dead economists like Milton Friedman and Adam Smith would uncover similar warnings that one of the greatest dangers of big government is its inevitable collusion with big business.

Even bloggers still living could help our two Times authors, as Walter Russell Mead did in a widely read essay responding to Greenberg’s article. Mead agrees with Greenberg that there is a “crisis of legitimacy for liberal and progressive thought,” because “if voters lose faith in the power of more govenrment to better their lives, the progressive era has come to an end.”

But Mead objects that Greenberg has a large blind spot. He assumes that the special interests now angering voters only exist outside the state. In this view, corporations and rich guys hire lobbyists and “pervert the state,” whose bureaucrats would otherwise do so much good. Greenberg fails to see that the state and its servants “constitute a special interest of their own.”

For large numbers of voters the professional classes who staff the bureaucracies, foundations, and policy institutes in and around government are themselves a special interest. It is not that evil plutocrats control innocent bureaucrats; many voters believe that the progressive administrative class is a social order that has its own special interests. Bureaucrats, think these voters, are like oil companies and Enron executives: they act only to protect their turf and fatten their purses.

(I’ll pause so Ford Foundation bureaucrats can regain their breath after being compared to oil company executives.)

Mead adds that progressives, in and out of government, don’t just want to “check the excesses of the rich” but also “to correct the vices of the poor…. From the Prohibition and eugenics movements of the early twentieth century to various improvement and uplift projects in our own day, well-educated people have seen it as their simple duty to use the powers of government to make the people do what is right.”

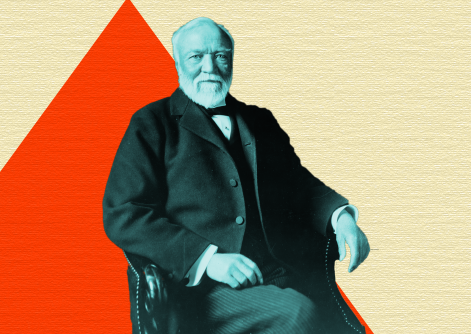

That rings true to anyone who knows the history of American foundations. Indeed, an entire book has been written on the most gruesome aspect of this phenomenon. Edwin Black’s War Against the Weak chronicles how Rockefeller, Harriman, and Carnegie funds flowed into eugenics, a movement that epitomizes the idea that some people can never be trusted to fend for themselves and should have their lives controlled -- and their bodies sterilized -- by persons with better educations and more advanced views.

Odd, isn’t it, that high-minded people who saw less privileged citizens as victims in need of rescuing ended up victimizing the least among us?